Belur and Halebeedu

This article appeared in March issue of Terrascape

One would not expect to find a 900-year old temple in a non-descript village with a tongue twister name like Doddagaddavalli. Driving past gently undulating vistas sparingly dotted with stout trees and small irrigation ponds – they added a dash of beauty to the widespread vegetable fields – I suddenly encountered a colourful sign by the road that announced the presence of an ancient temple. Turning off the main road and going past a small village with its usual share of chickens and cows that blocked my way, I found myself gliding from the top of a mound, down an easy slope. At the base of the valley was a small black structure of stone, a temple with shrines rising up from all its corners, a saffron flags fluttering over one of those projections. Its location could not have been better, situated at the edge of the village overlooking a lake and visible from every crest of the wavy landscape that surrounded it.

Lakshmidevi Temple at Doddagaddavalli

The Lakshmidevi temple at Doddagaddavalli is just one of the thousands built by the Hoysala Kings who ruled a large part of South India for more than three hundred years. Returning here again a few weeks later with a small group of history-enthusiasts, I saw a few eyebrows going up in amazement when I casually mentioned that the Hoysala Kings built 1521 temples in 948 centres. It is not much, considering that it averages to about five temples every year during their long tenure of governance. But what is impressive is that 434 of these temples have survived even today, with the oldest of them built more than 1000-years ago, the most recent having survived no less than 600-years.

Thanks to this temple building spree, the land here is dotted with ancient temples in every shape, size and varying degree of craftsmanship. Some of these have intricate carvings in stone and some have simple plain walls. While a few of these temples are in various stages of dilapidation, a few more have gone through modernization by the pious villagers who have continued the tradition of regular worship in the temples. Many of them are now managed by Archaeological Survey of India. The temple at Doddagaddavalli appears to have weathered the years without having to go through much change from its original shape. Its walls and shrines appear in near perfect condition, probably not a lot different from the way it looked in the time of the Hoysalas.

Doddagaddavalli was the first stop in my journey of exploring the Hoysala Heritage. I had set out from Bangalore on a sunny April morning looking for these ancient structures in stone spread around the small town of Hassan.

Leaving in the wee hours of the morning, I drove past the city that seemed to be perennially under construction, thanks to its double digit growth rate that has refused to slow down in decades. Beyond the city were industrial areas that spewed their smelly chemical exhausts on every passer by. Further ahead was a highway that lost the charm of its open roads to a widening work.

It took me good two hours before I could breathe clean and dust free air in a clutter free environment. The next three hours of breezy driving took me past small villages, fields, lakes and vistas containing hills and greenery, before arriving at Doddagaddavalli.

The temple here is a simple structure when pitched against the better known heritage sites built by the Hoysalas. Its four sanctums, the inner hall and its walls are a lot simpler than what one would see in Belur and Halebeedu, the erstwhile capitals of the kingdom. It also deviates from the typical architecture of the temples in these parts, which are constructed within a star-shaped pedestal. However, Doddagaddavalli’s charm is not in its work of art, but its setting next to a lake in an undulating landscape, completely devoid of tourists who throng the better known temples nearby.

I was almost transposed to the era of Hoysalas as I watched the life along the lake – men washing bullocks and women washing clothes, no one in any sort of hurry. My interaction with Puttaswamy, the watchman of the temple confirms the slow pace of life here. Still in late twenties, he had moved on from a busy life as a plumber in Bangalore, and had decided to come here and take it easy.

The Lakshmidevi temple was built by a merchant in 1113AD. This was one of the earliest temples built by Hoysala Kings, just a few years before they began dominating the Deccan Plateau. In 1116AD, King Vishnuvardhana defeated the Chola generals in Talakadu (near current day Mysore), ending a hundred years of Chola occupation in the region. Following this victory and his subsequent conquests in the north, he encouraged movement of artisans into his kingdom and commissioned construction of some of the most elaborately carved temples ever to come up in these parts, perhaps anywhere in the world.

Belur Chennakeshava Temple

Walking around the Chennakeshava Temple in nearby Belur next morning, I was amazed at the attention to finer details that went into making every statue carved on the walls and pillars. I found here a statue of a danseuse whose bangles were chipped to rotate freely around her hands, a carving of Nandi barely larger than a chickpea and a pillar decorated with miniatures of gods and goddesses probably numbering more than a hundred. The base of the outer wall was made of layers of friezes. One of these layers contained 650 elephants – every one of them carved differently from other.

Well known among all the richly decorated sculptures in Belur are madanikas, bracket figures installed below the awnings. The sensuous damsels are depicted in various moods and activities, like Shukabhashini talking to a parrot and Darapana Sundari adoring her own figure looking into a mirror.

A madanika figure

With carvings adorning every inch of the walls, pillars and roofing of the temple, it is no wonder that the sculptors took 103 years to complete its construction. But moving ahead into nearby Halebeedu, I was in for even more surprise. The twin temples of here are nearly twice as large as the one in Belur. It took nearly double the time to construct and hosts carvings that are no less intricate than the treasured beauties of Belur in their perfection.

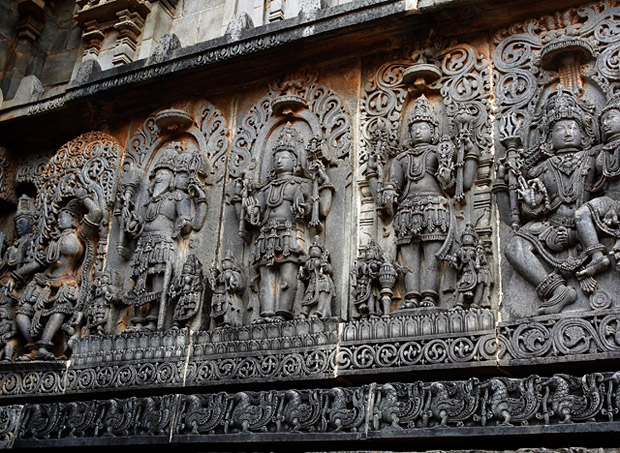

Carvings on the outer wall of Belur Temple

Taking a walk along the outer walls of the Hoysaleshwara Temple in Halebeedu, I was treated to a deluge of beauty in stone. Present along the outer wall were the finest engravings of images of gods and of events from Indian Mythology, all in the confines of a 4 feet high horizontal band.

One such figure is of Lord Krishna lifting Govardhanagiri to protect Gokula from torrential rains. I saw the ecosystem of the hill comes alive even in that little space. The architect had carved out in it a forest full of trees, a monkey climbing a tree, a hunter aiming at a pig and a lion looking out from its cave. Rendered under the shelter of the hill were the subjects of Krishna – cows, his cowherd friends and other villagers. All these may not be apparent to a quick passer by, but as the guides explained these nuances to tourists, I saw people pausing to take a closer look and gasping with awe. Another similarly detailed section of the wall showed Ravana attempting to lift Kailasa Parvatha, the expression of his face clearly showing his suffering under the weight of the mountain.

Carvings on the outer wall of Halebeedu Temlpe

The one figure on the wall that awed me the most was of Lord Shiva as Gajacharmambaradhari – an appearance where the lord dances inside the body of a demon in the form of an elephant. I found it difficult just to imagine the concept, but the sculptor depicted it effortlessly in an elegant manner. There is so much attention to detail in this work of art; I could even see Shiva’s finger nails shown piercing through the skin of the pachyderm.

Walking me along these marvels of art, my guide Uma occasionally slipped in carefully practiced humorous quotes. Pointing at an image of a monkey pulling drapes of a lady, she winked and declared it as ‘monkey business’ and watched with delight as a short group of tourists burst out laughing at the remark. In another instance, she asked me what is God, and waited for me to come up with an answer. Not expecting a question from someone who should be giving me answers, I paused, not knowing what to say. She then showed me figures of the trinity on the wall – Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva, and explained me – “G-O-D god; it means Generator, Operator and Destroyer!”

Nowhere before had I seen so many images of stone carved to such great detail. How did the Hoysala architects manage to bring in elaborateness in stone that was achieved by none else, not even by their contemporary neighbours? It is Uma who unfolded the mystery to me. “The temples here are built using soap stone,” she told me, “this type of stone is soft like butter when it is taken out from the earth. It hardens over continuous exposure to the atmosphere.” With its butter-like characteristic, the stones could be carved to greater details, a task impossible with any harder form of stone.

It would not be easy to believe that a stone could be so soft. But I was to see a demonstration very soon. Outside one of the temples, I was surrounded by hawkers selling postcards, small metal statues and artifacts made of stone. I managed to escape from them without buying anything, but a friend bought a small grinding stone that happened to be made of soap stone. Its surface was so soft, we could easily make scratches and marks on it using fingernails!

Halebeedu is not just about its famed Hoysaleshwara Temple. Few people who come here realize that the place is littered with the remains of the ancient kingdom. It was the capital of the Hoysalas for most duration of their rule, complete with bustling markets, temples and housing colonies. We can still see remains of the old habitat – a large area strewn with carved rocks and remains of the pedestals of a few temples. Also within the fortification of the town are three Jain Bastis and Kedareshwara Temple – a smaller replica of Hoysaleshwara Temple built by Vishnuvardhana’s grandson.

The Jain Bastis at Bastihalli

My prized discovery of Halebeedu turned out to be none of these grand structures, but a small kalayani in the village of Hulikere. It is an ornate tank hidden inside a coconut grove. The Kalyani’s waters are surrounded by small shrines of stone in all the eight directions, giving a reverent feel to the tank. Its calm waters reflected the tall coconut trees and the puffy clouds in the sky. The steps leading into the water served as perfect place to rest and watch the fish gently moving in the still water. I sat there for a long time all by myself, with no one else but fish for company. The silence here was so filling for the heart, I would never have bothered to leave but for my greed to explore more.

The kalyani at Hulikere

About 12km from Halebeedu is another temple at the small village of Belavadi, again hidden from the weekend crowds and day-trippers. On my way here during another visit in the middle of the monsoons, I was welcome with carpets of yellow sunflowers that were splashed amidst lush greenery, often larger than several football fields joined together. Occasional marigold fields added further to the riot of colours. Silhouetted far away to the west were the hills of Western Ghats that rose from the plains and merged with monsoon clouds. A gentle drizzle constantly reminded me of the wet season.

Sunflowers blooming

When it comes to intricate carvings, Veeranarayana Temple at Belavadi does not compete with Belur and Halebeedu. The temple’s prized possession is its 108 circular pillars that are polished so well that I could see my own reflection on their surface. An array of these pillars leading to the sanctum makes the temple look as grand as a king’s court.

Belavadi Veeranarayana Temple

When I needed a break from hopping from temple to temple, I found refuge in a coffee estate in the small village of Bikkodu near Belur. It was located at the edge of the plains where barren landscape made way to an evergreen canopy. The estate, with many tropical trees preserved intact to provide shade for coffee plants, was home to birds with dazzling colours and beauty. In my two hours of wandering in this green expanse, I saw crimson coloured scarlet minivets, green pigeons, emerald doves, rose ringed parakeets, coucals and a few dozen other colourful birds that whizzed past me as though they were getting late for an appointment. If the walk under the evergreen forest refreshed me, coffee made from freshly ground powder offered by Vipin, the estate manager, kept me going further.

A coffee estate near Belur

My last stop in the journey into Hoysala heartland also happened to be in a coffee estate. Searching for the origin of these kings who were connoisseurs of art in stone, I arrived at the small village of Angadi in the heart of Sahyadris. It was here in a small temple that a brave young man killed a tiger with bare hands and subsequently scripted the creation of a kingdom. His descendants moved to Halebeedu and established a capital, from where they ruled a large part of Deccan for more than three hundred years.

Patala Bhairava Temple at Angadi

Still standing proudly inside a coffee plantation in Angadi are three small beautiful temples that are said to date back to tenth century. The temples do not compare against the grandiose structures built in the later days, but it is here that the story began in a small way. As I departed from Angadi on my way back Bangalore, I wondered for once how every creation of greatness has a very humble beginning.