Camobodia – Life After Khmer Rouge Genocide

Walking the long wooded path towards Beng Melea Temple, I heard a mild sound of music coming through the air. It grew on me as I closed-in to its source – a bunch of uniformed men on a raised platform not far from the temple entrance. From a distance, something appeared to be wrong. As I got nearer, I realized that some of them were missing an arm, some were blind and some wore artificial limbs. A sign nearby informed that they were the victims of Cambodia’s landmine problem, making a living playing music for the tourists visiting the temples. There were music CDs available for $10 or if you did not want to buy one, you could always sit and listen and leave a donation.

Angkor Wat Temple in the tropical jungles of Cambodia. On the approach to some of the temples in the region, you will meet musicians who were victims of landmines planted across Cambodia in the seventies and eighties.

This was my first encounter of victims of Khmer Rouge’s days. From the days of civil war many decades ago, landmines buried across the country, especially in border areas, had claimed thousands of victims. Although a large number of them have been de-mined now with great effort, they still lurk in the remote jungles and occasionally explode on an unsuspecting rambler.

Cambodia’s troubled history associated with landmines dates back the seventies, when the country witnessed a bloody battle between Khmer Rouge soldiers led by Pol Pot and the military government headed by general Lon Nol. Phnom Penh was captured by the Pol Pot’s fighters in the summer of 1975. It was a turning point in the country’s history. When Phnom Penh fell, people in the city cheered the red army walking the streets and hoped for good days ahead. But what transpired was years of suffering that no one had hoped for.

As soon as he took power, Pol Pot ordered everyone to leave the city to work in the countryside. Anyone who was capable of reasoning–the well-educated, teachers, artists, government officials–were treated as enemy of the state and was punished for their intellect. They were incarcerated, tortured to confess to crimes that they did not commit and eventually found their way to one of the many killing fields across the country. People who were made to leave the city were led to work in rice fields in exchange for nothing, often fed just enough to survive.

The cave at Phnom Sampeau, one of the many killing fields of Cambodia. During the days of Khmer Rouge, many people were killed here by the regime by throwing them into this cave from a height.

As the regime of Pol Pot ruled on Cambodia, external forces continued to abet fighting in the country, primarily led by Vietnamese Army. To impede the movement of enemies, all the parties involved in the raging war took to the aid of landmines. Much of Cambodia, especially the north-eastern areas bordering Thailand were carpeted with mines.

Khmer Rouge’s rule lasted only for four years, when the Vietnamese overthrew them and drove them to the jungles. The battle continued for many more years although their days in power ended in 1979. The landmines however, continued to haunt the population. A concerted international effort helped weed away a large number of mines, but they still continue to explode against unsuspecting people.

The amputees at Beng Melea and other temples are a tip of the iceberg, perhaps the only survivors of mines that the fast-moving tourist population gets to see. Much of Cambodia, it appears on the outset, has forgotten the difficult history and surging ahead into a brighter-looking future. But there are still occasional landmines bursting, and there are still stories of hardships across the country that are not forgotten.

My journey across the country made me a witness to some tragic stories of its past and present. I once stayed at a small village just two hours drive from Siem Reap, living with a family and enjoying the green tropical countryside. Next morning, I went for a walk with my Cambodian friend and visited a family living at the edge of the village. The story told by the lady of the house troubled me deeply. It was only a few years ago when her boy had wandered off the jungle while playing with his companions. At some point he had stepped on a landmine and the explosion immediately took his life.

The beautiful tropical village near Siem Reap, where I met the lady whose son was recently killed by landmines.

She narrated all this with a gentle emotion-free smile that did not have any lingering bitterness. She kept no grudge against the wrong-doers and appeared to have long since forgiven the forgotten the incident. But learning about it did leave a mark in me. It is one thing to read statistics about number of landmine victims in a faraway country and another to be talking to someone who suffered from it.

While there are people who suffered from the landmines across the country, a larger number of people suffered directly or indirectly from the fighting that lasted for many years. While visiting the small town of Kampong Chhnang just north of Phnom Penh, I met Kim, a tuk-tuk driver who catered to the few tourists who visit the town. Kim was a bit of an introvert who spoke in a soft voice when he had to. He appeared very hesitant in every action, very unsure about every word he said. When he smiled, which he did often, it seemed like a difficult attempt to erase the unhappy memories from the past. It never occurred to me that this hesitation had a story from the past until he opened up to many of my questions.

Kim, my Tuk Tuk driver at Kampong Chhnang, who ran away to refugee camps at Thai-Cambodia border during the Khmer Rouge regime.

When the fighting broke in the seventies and life in Cambodia was becoming tough, he ran off towards Thailand like many of his countrymen. At the Thai-Cambodia border, he lived in a refugee camp all those years, often very close to the battleground and sometimes running from camp to camp. Those years were hard, where nothing was predictable and no one could tell what happens tomorrow. He was taught English in the camp, which came to use in the later years. When peace returned to Cambodia, he came back to Kampong Chhnang to make a living as a tuk-tuk driver for tourists. Unlike the lady who lost her child, it appeared that the scars of the war had still remained deep inside him.

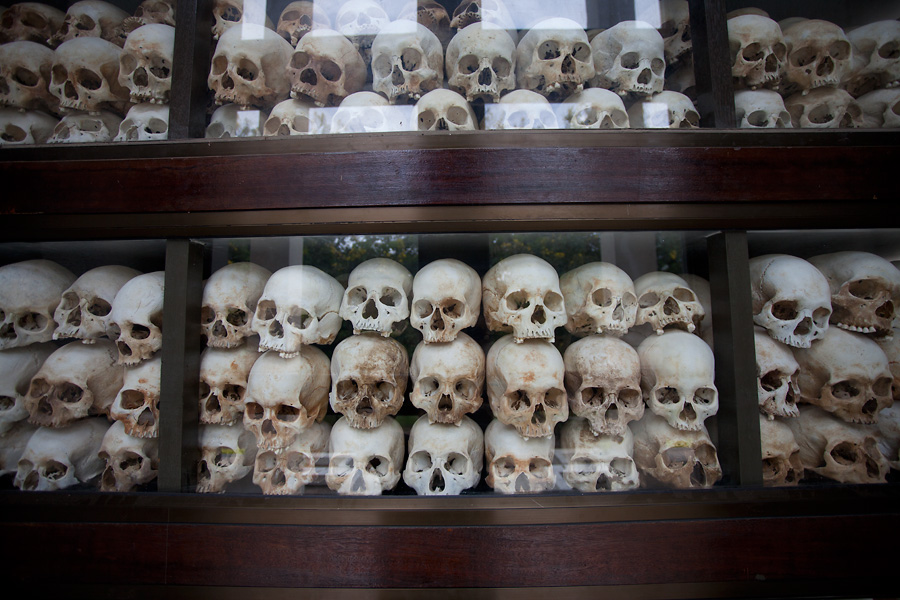

The extent of damage and the difficulties suffered by people of Cambodia is evident from two infamous sights of Phnon Penh – Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum and the Killing Fields of Choeung Ek. Tuol Sleng, once a high school, was converted into a prison by Khmer Rouge authorities. Today, the place is a museum that displays the tiny prison cells and describes the torture that the captives went through. The prisoners convicted of treason were taken to Choeung Ek, one of the many places across Cambodia designated for executions, now referred to as Killing Fields. Choeung Ek now is a moving display of the remains of the dead, including five thousand skulls stacked into a stupa, and the sites that remain witness to the worst cruelty that people of the country had to suffer from. An excellent audio guide provided to visitors offers a glimpse of those difficult times.

The remains of Khmer Rouge’s cruelty at Choeung Ek Killing Fields and Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum

Despite all that happened in that past, and despite those memories still haunting the survivors, much of Cambodia has moved on. Tourism and foreign aid has, to some extent, helped Cambodia emerge from its dark days and stride into the new world. Phnom Penh is now a bustling city with tall buildings that host frenzied economic activity. Siem Reap is a tourist hub that sees visitors in millions year after year. People in urban areas are busier than ever, some working hard to make ends meet and some working hard to get richer. In the rural areas, it’s a quieter life of farming and fishing that keeps people occupied for much of the year. The scars of the past may not have healed completely, but no one has the time or interest to reopen the old wounds.