Here is a collection my images of winters in Ladakh, made over several visits in a span of about 7 years. Originally posted on medium.com – Winters in Ladakh — India’s ultimate landscape photography experience!

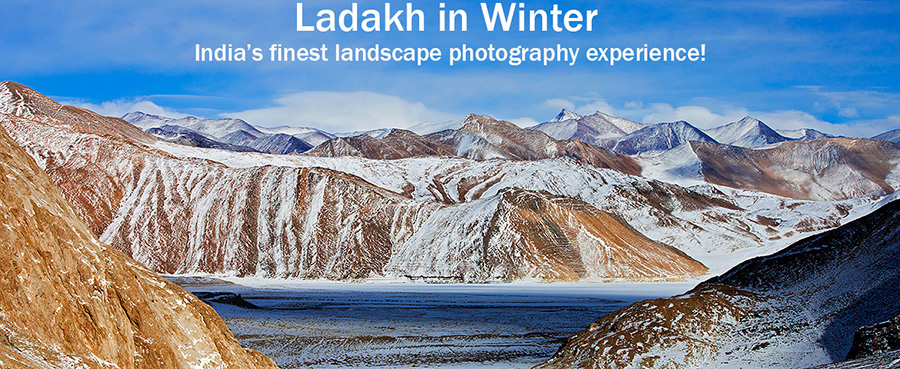

Powdery snow on the mountains over a frozen Pangong Tso Lake, in Ladakh during winters.

I first visited Ladakh exactly ten years ago. This was well before the region became every motor-cyclist’s ultimate destination, part of every traveller’s tick-off list and every holidaymaker’s check-in dream. In those days, tourists were in smaller numbers and Leh had more homes than guesthouses and hotels.

Every winter, we conduct a photography tour to see and capture the glorious landscapes of Ladakh. This is perhaps India’s ultimate landscape photography experience. Travel to the highlands of Ladakh in winter, when Ladakh is at its pristine best — with its snow-clad mountain landscapes, frozen lakes, resilient nomads with their herds of sheep and yaks and endless fields of snow. Explore photography on the roof of India on this mentored photography tour in a season when the earth is covered in a carpet of snow. See details and sign up today: A Snow-filled Winter in Ladakh — Photography Tour

The story is all different now. Ever since a block-buster Indian movie featured the landscapes of Ladakh eight years ago, it has become the go-to destination of hundreds of thousands of people every year. The region has been transformed from a quite mountainous escape to a bustling tourist town of German bakeries, pizza joints and mall-roads!

But all that ends when the summer season makes way to a cold frigid winter in Ladakh. After September, as the temperatures start falling rapidly, shutters are downed on the souvenir shops. Most hotels close for winter and taxi drivers stay home for a few months. But this is also the time when mountains are transformed through the magic of falling snow.

As we drove higher and higher–well above 12,000 feet–there was a visible change in the geographical features. The brown slopes of the mountains that adorned a hat of snow on the peak morphed into all-white walls bifurcated by a rough patch of road that allowed us an access. Below us, at the bottom of the valley, melt-water gushed away, making a long journey into the plains that nurtured the civilization of a billion people. Up here, the only sound of life came from the inhabitants of our own car, save for an occasional yellow-billed chough that flew past or a cuddly-looking marmot that scooted away on our arrival. Glaciers dotted the landscapes, adding more force to the river that skirted past their mouths. The enormous tall massifs covered with snow hurt our eyes, and yet, pleased our souls through a sense of calm and magnanimity effused from them. Someone in the car said, “we have reached heaven”. I could not help but nod silently. I did not want to speak up and break the indulgent muses of my mind.

It was a summer afternoon and we were driving towards Penzi-La, the mighty pass that rose above 14,000 feet to partition the valleys of Suru and Zanskar. I was leading a photography tour comprising a dozen trigger-happy people who were willing to go through any struggle to be a part of this gigantic landscape. For past three days, we had come away from the networked world and were camping amidst high mountains, disconnected from everything else but the grandest showcase of nature. We had traversed in the shadow of Nun and Kun mountains, both massive projections from the ground that climbed well above 20,000 feet, covered in megatonnes of snow that shined in the bright mountain sun.

I found my ideal do-nothing place in Ladakh’s Nubra Valley. It was a place for long walks in the meadows, reading books with a cup of tea in a garden chair, eating seabuckthorn fruits on the riverbed, relishing apricots straight off the tree, hiding behind the bush watching a herd of Bactrian Camel in the wild, chasing shepherds, walking along the river and watching sunsets while listening to sweet sound of the flow. The days in Nubra were filled with activity and yet I wasn’t really doing anything.

A wise man once said, “Happiness is like a butterfly which, when pursued, is always beyond our grasp, but which, if you will sit down quietly, may alight upon you.” Travelling has some semblance with this statement. If we run from place to place seeking excitement and new experiences, those pleasures always seems to be someplace other than where we are. We humans need change of place at times, but making it a mission to keep changing places probably doesn’t work. The proverbial butterfly requires that you rest.

That place to rest, I found in Hunder. It’s a tiny village in Ladakh’s Nubra Valley housing a few dozen families, and when I went there seven years ago, had only a few dozen tourists. My guest house had a room big enough to play badminton, and outside in the garden, you could actually play football. The garden, however, was put to a more idyllic pursuit. With a book in one hand and a cup of tea in the other, I could sit under the apricot trees and while away the entire day, sometime shifting into the sun and sometimes returning to shade. And when I had enough of the book, there were other hedonistic pursuits that are hallmark of an aimless traveller.